Gorilla habitat may be located where?

FAQ-Gorilla Trekking in Uganda and Rwanda, Mountains gorillas live in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, and Uganda. Volcanoes National Park in northern Rwanda has mountain gorillas from the nation.

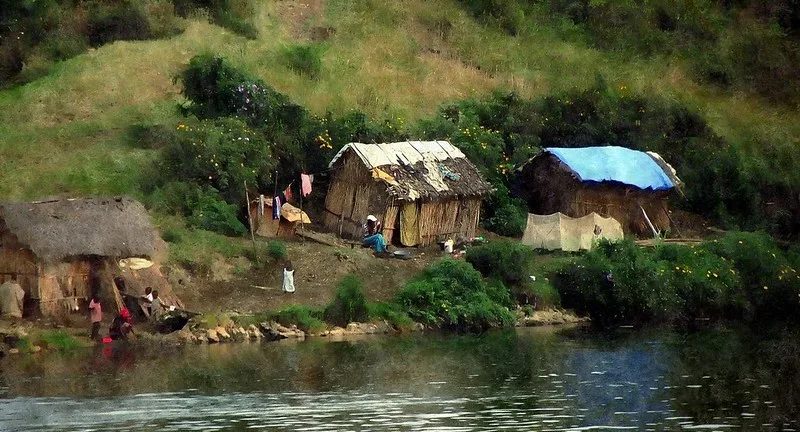

Living in Mgahinga National Park and Bwindi Impenetrable National Park in the southern western region of Uganda, the Mountain Gorillas of Uganda On the western end of this vast nation, Virunga National Park has DRC gorillas.

These three nations share three National Parks spread across the Virunga volcanic mountains. These common National Parks include Virunga on the Congo side, Maghinga in Uganda, and volcanoes in Rwanda. One of few Bwindi Impenetrable National Parks not entirely in Uganda.

For monitoring gorillas, what nation is best?

The argument about which nation is best for gorilla trekking has been ongoing so that visitors may decide.

For a gorilla trip, how many days—at least—do I need?

For your gorilla hike, it is advisable to spend three days either in Rwanda or Uganda. Traveling to the park should occupy the first day. The second day for gorilla trekking and the final day for returning to the airport for your trip out.

Although it is feasible to travel back to your nation more notably when trekking in Rwanda, there is no assurance that you will return early from your gorilla trip to let you transfer to the airport and arrive in time for your international flight out.

A gorilla permit costs how much?

Currently, a gorilla permit in Rwanda is USD 1500.00 per person per trip and USD 800.00 in Uganda. Sometimes Uganda via Uganda Wildlife Authority discounts gorilla licenses at USD 800.00 per person during low seasons. Low seasons in Uganda are those of April, May, and November. If you would like to seize this chance, get in touch.

Included in a gorilla permit’s purchase is what?

A gorilla license lets you spend one hour with habituated mountain gorillas in each nation, accompanied by park admission fees and a guide. Although seeing the gorillas may take anything from thirty minutes to eight hours, once you locate them you will be granted one hour with them.

How would I arrange gorilla permits?

Uganda Whereas Rwanda Development Board issues gorilla permits from their main office in Kigali, Uganda Wildlife Authority issues gorilla permits from their head office in Kampala. Although you may book your permission straight from either office, it is advisable that you contact Uganda or Rwanda tour companies for your gorilla permit to prevent bureaucracy and waste of time.

Most tour providers charge nothing to reserve gorilla permits; most importantly, if you buy a trip with them, they cannot ask a modest price unless you specifically want them to arrange for you.

For my gorilla walk, what should I pack?

Whichever family group you visit, you might have to go a great distance in hilly, muddy terrain under perhaps rainy circumstances before you come across any gorillas. On your strongest shoes, To guard against aggressive stinging nettles, wear long sleeved shirt and heavy pants. Since it is sometimes chilly when you begin out, start with a sweater or jersey .

The gorillas are rather accustomed to humans, hence your choice of colors makes little difference. If you have pre-muckied clothing, you may as well wear them; whatever clothes you wear to go tracking are probably rather muddy; you slide and slither in the mud. Old gardening gloves can be very handy when you are reaching for handholds in rocky terrain.

Carry as little as necessary—ideally in some kind of waterproof daypack. While sunscreen, sunglasses, and a hat are a great idea at any time of year, a poncha or raincoat could be a useful addition to your daypack during the wet season.

During a lengthy journey, you could possibly feel like a snack, and you should definitely pack enough drinking water—at least two litters. Locally, the lodging buildings sell bottled water. Particularly in the rainy season, make sure your photographic equipment is well covered; if your bag is not waterproof, wrap your camera and films in a plastic bag.

You don’t need binoculars to see the gorillas. Though in fact only the most committed are likely to make use of them, the theory suggests that bird watchers would prefer to bring binoculars; the hike up to the gorillas is usually quite directed, and going up the steep slopes and the dense forest tends to engage one’s attention and mind.

Bwindi National Park boasts how many habituated gorilla families?

At Bwindi, there are twelve habituated gorilla families; after the habituation process ends, each family gets a name. These include Mubare, Habinyanja, Rushegura, Bitukura, Kyaguriro, Oruzogo, Nkuringo, Mishaya, Nzongi, Kahungye, Bisingye, and Bweza.

Where in Bwindi National Park will I stay depending on gorilla permits?

Different areas of habituated gorilla families in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park mean that, should you be ignorant of this, you might book incorrect lodging or hotel. Among these areas are the South (Ruhaga and Nkuirngo), the East (Ruhija), and the North (Buhoma). If you purchase northward permits, kindly arrange lodging in the North; the same holds true for the other areas. Please call us for more details.

When should one undertake gorilla trekking?

Although mountain gorillas may be seen all year long, the drier months of June, July and August plus December, January and February are most sought after times. Changing global temperatures make it difficult to predict when it will rain or not.

For what age range is hiking gorillas limited?

The lowest age limit in Uganda and Rwanda is fifteen years. Should the authorities question your age, you might be obliged to provide your passport or birth certificate. If you want to hike gorillas and are traveling with youngsters, make sure they are 15 years or above.

Bwindi National Park is situated where?

Bwindi Impenetrable National Park is unlike other gorilla national parks; it is situated in southern Uganda. Three Kabale districts, Kanungu, and Kisoro share it. From Entebbe Airport to several Airstrips in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, it is around 500 kilometers from Kampala and takes eight to nine hours driving or one hour flying.

How are visitors assigned gorilla families?

Allocating gorilla families to visitors is a policy shared by Uganda and Rwanda. You purchase by area when purchasing gorilla permits in Uganda. For instance, Uganda has four regions: Buhoma in the north, Ruhija in the east, Rushaga and Nkuringo in the south. Every area raised gorilla households.

Depending on their physical condition, each visitor will be assigned to a gorilla family of their choice on the day of gorilla trekking; other considerations like whether you wish to trek with friends or family, whether you wish a family with children, or a family with many silver backs; hence, you will need to inform the gorilla guide your interest and they will try to assign you a gorilla family that fits your interests.

Could I visit Bwindi National Park using public transportation?

One might rather easily go from Kampala to Bwindi Impenetrable National Park via public transport. Although this is feasible, among other things there are several hazards associated with delays and theft of your assets.

There are what numbers of mountain gorillas worldwide?

The most recent gorilla census indicates that there are 880 mountain gorillas in Bwindi Impenetrable alone; three of these National Parks share the virunga volcanic ranges; the rest are shared between Volcanoes National Park in Rwanda, Virunga in Congo and Mgahinga in Uganda.