The politicians of the Northern Ruhengeri Gisenyi axis

The Northern Hutu was instrumental in toppling the Tutsi, but upon independence in July 1962 the Belgians delivered the keys of power to a southern alliance.Out of this group Gregoire Kayibnada became the first president of the new nation. A moderate preaching Hutu unity, Kayibanda oversaw a regime marked by widespread Tutsi persecution.

The administration also gave the preferred central and southern regions an excessive percentage of the little foreign investment the country received. Ten years of seeming regional indifference and national decay followed, when the Northern Hutu once again intervened.

A bloodless revolution placed Juvenal Habyarimana as president of the second republic on July 5, 1973, the act that resulted in Idi Amini being held hostage at the Entebbe airport as Peace Corps volunteers. Under house imprisonment, Kayibanda died of severe alcoholism some years later.

The politicians in the Northern Ruhengeri Gisenyi axis were a dynamic team. Once they felt at ease in charge of their own affairs, they opened their doors in the middle of 1970s and laid welcome mat for outsiders. The earnestness of their hosts amazed Belgian, Swiss, French, and German benefactors.

The image of Rwanda as the “Switzerland of Africa” stable hardworking, beautiful started to grab hold. Most westerners would have found the rigorous quota system—under which Tutsi were assigned 10 percent of all government posts and school vacancies based on their ethnic presence in the population—to be unacceptable.

Still, even this was seen as a progressive stance toward minorities in contrast with those in other African nations at that time. Many saw Habyarimana as the type of benevolent tyrant the continent needed to develop. The Rwanda narrative touched the hearts and relaxed the purse strings of outside financiers.

Even the US Agency for International Development was intending to create a complete office in Kigali by 1978. Development aid poured at before unheard-of rates, and the increasing flood lifted everything. But typically, Ruhengeri and Gisenyi were the targets of the most richest initiatives.

The Habyarimana administration took several much-needed efforts in addition to being a passive beneficiary of international aid. Its budget included over half for agriculture. After a period of neglect during the first republic, Rwandans once again paid close attention to their land resource base after their post-independence era.

In the first five years, six thousand kilometers of terraces and hedgerows were constructed or repaired to provide approximately one fourth of the current arable land base more erosion protection. Millions of trees were added annually beginning in 1975. Mostly Rwandan funding and work supported both projects.

Less than one hundred miles of paved road covered the whole nation when we arrived early in 1978. Two years later, a peculiar group of donors—including Italians, Libyans, and Chinese—planned and funded a grid encompassing all important arteries.

Second only to agriculture, the new government significantly funded education, spending more than one quarter of its yearly budget in support of institutions and schoolchildren. By the late 1970s, still less than half of all qualified Rwandan children attended elementary school; one kid in fifty attended high school. Lack of instructors was one of the issue; lack of a classroom was another.

Clearly not for disempowered Hutu pupils, the colonial rulers had not invested in this field. Launched in 1979 to improve classroom access and make the curriculum more relevant to Rwandan needs, a bold program of educational reform was The first graduates of the new program would come from high school and college in the late 1990s without any delays or obstacles.

Spending on public health was relatively modest. Slightly better than the 29 percent death rate for young gorillas, just 6 percent of the yearly budget was allocated to this sector, almost none of it for family planning in 1978 about one fourth of all Rwandan children perished before the age of five.

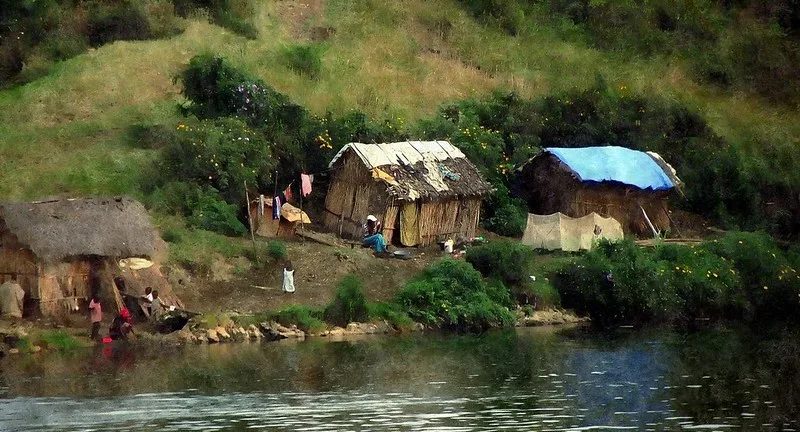

Still fertility rates for women of reproductive age reached the biological limit, and the total human population was expanding at 3.7 percent annual. With around five hundred people per square mile, Rwanda climbed at the top of rankings of the most densely inhabited nations on Earth. If one only considers agricultural areas, the density rising to more than 1300 per square mile is rather pertinent in a country where 95 percent of the population lives off what they can produce on declining rural acreage.

The typical farm size was down to an acre; most family plots were not being further subdivided via inheritance; instead, framers were becoming intense gardeners. In a tiny landlocked country dependent mostly on coffee and lacking resources, there were few other growth possibilities.

The Habyarimana administration established the office Rwanda is du Tourism et des Parcs Nationaux (ORTPN) in 1974 as one of its first activities.This eliminated conservation from the ministry of Agriculture, which had authorized the 1969 25,000 acre Virunga parkland expansion for pyrethrum production.

It also provided fresh focus to the growth of the travel industry as a component of the national economy. But by 1979 the growing wave of human habitation once again lapped at the Virunga coast. Land hungry farmers gazed with longing at little remained of the PARC National des Volcans. Western donors had money to spend, and northern politicians were all too happy to follow the interests of their constituents as well as their own.