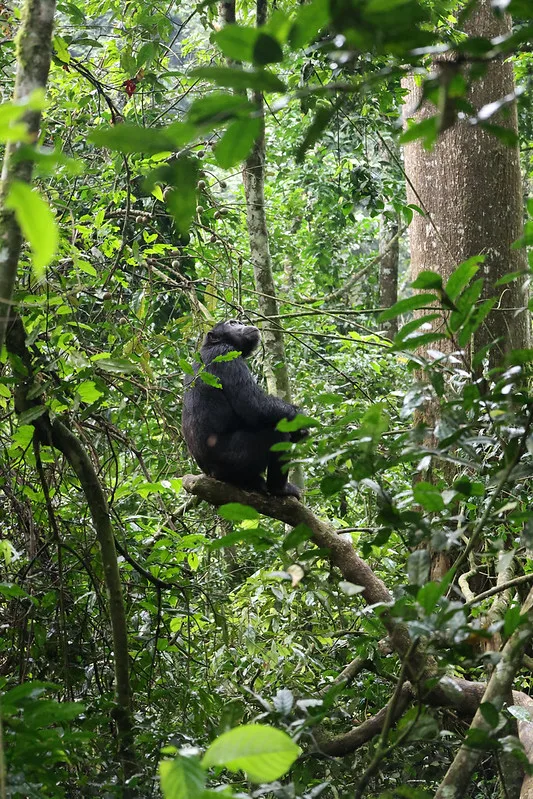

Booking gorilla trekking safaris in Uganda and Rwanda with Katland Safaris.

Katland Safaris organizes the best gorilla and wildlife safaris in East Africa. When it comes to gorilla trekking, we will book your gorilla trekking permits for Uganda`s Bwindi and Mgahinga gorilla national park and gorilla permits for Volcanoes National Park in Rwanda. Besides booking your gorilla permit, we will also put all other gorilla safari accessories, like transportation and accommodation, in one package to make your gorilla trekking safari a memorable adventure:

Your gorilla trekking safaris can be customized to meet your safari expectations and needs, and budget. The safari package can range from budget, mid-range, and luxury safaris.

Feel free to contact our team of excellent safari consultants to help you organize the best Africa gorilla safari ever.

Embark on an unforgettable Gorilla trekking and wildlife safari experience in Uganda and Rwanda.

WhatsApp us at +256705778866 to book your safari today!

Email us at info@katlandafricagorillasafaris.com for more information

Visit www.katlandafricagorillasafaris.com for exciting tour packages and itineraries

The Uganda Wildlife Authority issued a decree on March 25, 2020, that halted all tourism-related operations in the nation. “Until April 30th, all tourism and filming activities involving primates and other wildlife are to be put on hold,” said UWA director Sam Mwandha. We don’t know the virus’s origin or the potential consequences of primate infection; therefore, this command was issued to halt the activity until we do.

The Uganda Wildlife Authority issued a decree on March 25, 2020, that halted all tourism-related operations in the nation. “Until April 30th, all tourism and filming activities involving primates and other wildlife are to be put on hold,” said UWA director Sam Mwandha. We don’t know the virus’s origin or the potential consequences of primate infection; therefore, this command was issued to halt the activity until we do.